History of Ancoats Hospital

Up until 1825, the Manchester Infirmary (situated in Piccadilly since 1755) had been the only medical institution in the city. Attracted by the prospect of work, people flocked to the city and the population of Ancoats alone increased from 11,000 in 1831 to 56,000 in 1861.

Ancoats was built in a hurry to house the thousands of workers and families who came to work in the mills and factories. Medical needs outran supplies and the Ardwick and Ancoats Dispensary was one of three medical charities (alongside Salford and Chorlton upon Medlock) to provide medical services.

Renowned throughout the country, the Dispensary was the workplace of James Kay who was one of the first doctors to work at the Dispensary in 1828 and later went on to write his famous book ‘The Moral and Physical Conditions of the Working Classes (published in 1832 in response to the cholera epidemic) employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester’. In his book, he wrote “I was brought into contact with one of the poorest parts of Manchester, inhabited in the main by Irish labourers and factory workers. Manchester in 1828 was an accumulation of social evils. Lack of sanitation resulted in cellar dwellings so poorly drained that the floors were often underwater and sometimes I had to walk on bricks to reach my patients’ beds with dry feet. Streets were where refuse was dumped [and there was] no supply of water, no drainage, no control of slaughterhouses, no protection to women and children in the factories. These were the conditions of the poor in Ancoats Manchester. The workers lived to a great extent upon oatmeal and potatoes, spending their surplus earnings on drink and especially on whisky.”

As the cholera epidemic spread across Europe, it soon reached Manchester and it was only owing to James Kay and his writings that precautions were taken. A voluntary committee was set up, houses were visited, unsanitary conditions reported, streets were scavenged and lodging houses whitewashed. Temporary hospitals were set up and medical officers appointed to each. As a result of this, Kay was in charge of the Knott Mill Cholera Hospital. In his book, Kay continued to describe the conditions around a group of houses lying immediately below Oxford Road and almost on the level of the polluted Medlock. These houses belonged to a colony of Irish labourers and consequently came to be known as ‘Irishtown’.

The epidemic and the conditions left a deep impression on James Kay and it was he who was mainly responsible for the introduction of a better way of handling social problems. The Manchester Statistical Society began investigations into conditions of the poor as well as the provision of education.

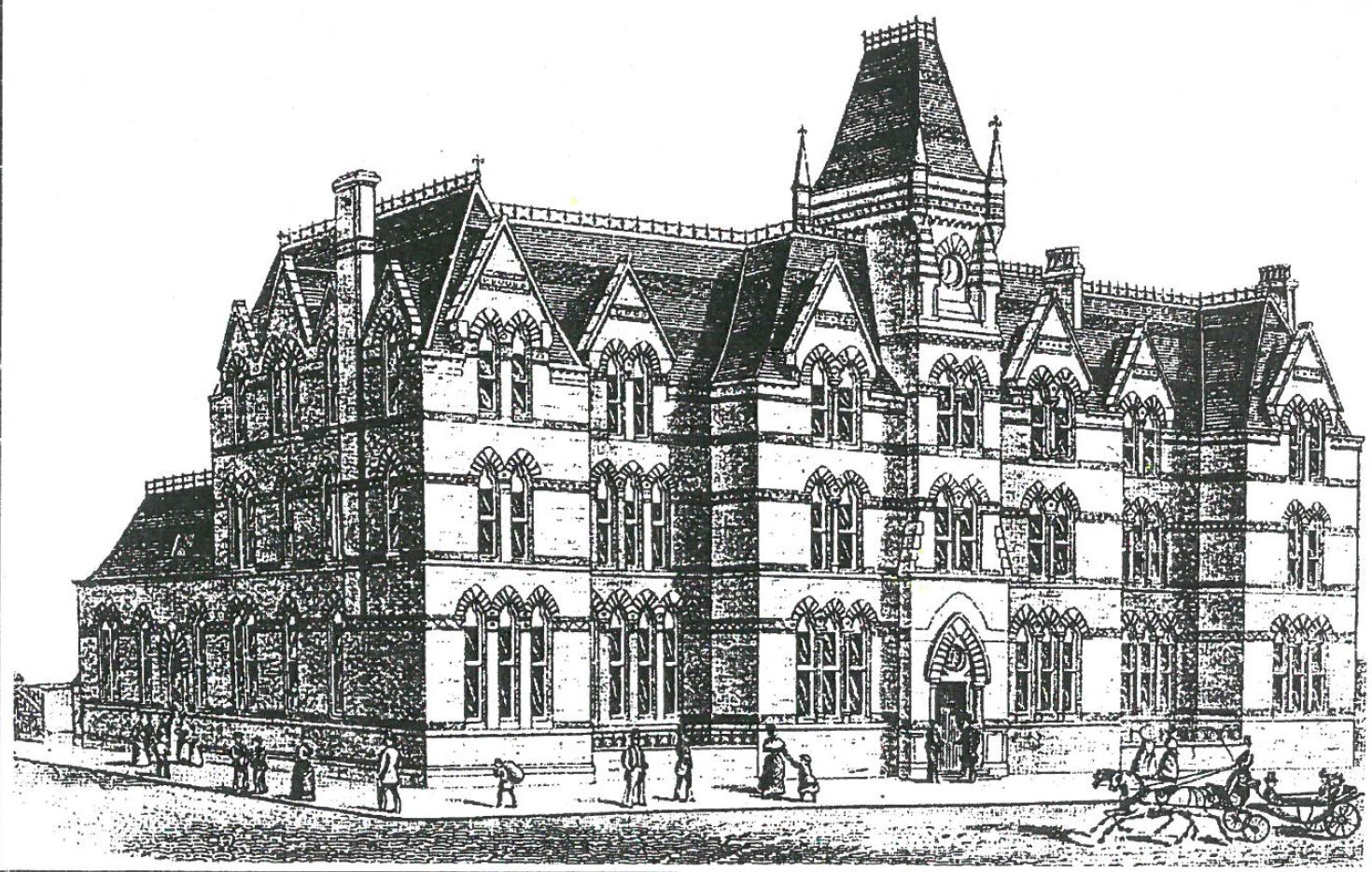

The Ardwick & Ancoats Dispensary opened in 1828 at 181 Great Ancoats Street. In 1850 it moved to Ancoats Crescent at 270 Great Ancoats Street. Within all of these premises, it provided a basic level of healthcare for the benefit of the labouring poor. In 1872 it moved to its present site on Mill Street and for the next century was a beacon of hope for thousands. It was formally re-opened in 1874 following a bequest from a Miss Hannah Brackenbury of £5000 plus £2000 associated costs which allowed the hospital as we know it to be built.

It was a Venetian Gothic Revival design with polychromatic brickwork, a saddleback roof and a distinctive central tower together with a clock face. The architect was Daniel Lewis, a young architect from North Wales who, perhaps due to his premature death at only 33 years old, is rarely mentioned amongst Manchester architects.

The building itself was granted Grade II listed status in 1974 and in 2011 was listed by the Manchester Victorian Society as one of the 10 ‘most at risk’ buildings in England and Wales.