Andy Hickmott, our Poet in Residence

It was during this period that Andy Hickmott, who was completing an MA in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University and studying poetry under the direction of the Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, offered to become our ‘Poet in Residence’.

Andy became so inspired by the story of the Dispensary that for one of his final pieces of work he wrote a book of poetry entitled in: dispensable. The italic is not a mistake but the way Andy has named his book. Andy had his book published and donated copies to ADT to sell at fundraising events. These are a few of his final poems about the Dispensary with ‘Annie Coates’ as the building.

The New Mrs Coates

(1874)

No one remembers Annie’s maiden name nor the street from which she wedded came, though, for sure, folk there must’ve hung the same grey saggy nets behind their peeling sashes, with steps a man paints and his woman washes (flaked and caked now as once were Annie’s)— streets in the shadows of smokestacks steaming, streets you wouldn’t dream of being seen in for fear of young fellows minded for scuttling; streets that breathe like an asthmatic lung— coughing out spent flesh through distraught iron gates, drawn back at next shift, and closing time. No one remembers the fuss that was made of her coming, the hoop-la proclamations said then carved on a stone they set over her head.

Fetch Mrs Coates!

(1915)

She arrives on a clatter of cobbles, her coming announced by clank of chain, by ominous knocking. She’s found us, the one house down our street tonight with a light on. Her pinioned black bag fills us with jitters of hope and dread.

She nods to white flags flapping outside— women’s labour is everywhere screaming. ‘Gave him a royal send-off?’ she jokes. ‘I hope he’s quicker to pull on a gas mask.’ Sends the sister’s eldest to the standpipe, tells the old woman to warm the stove.

She follows the screaming to the lying-in, sets down her bag, clears the dresser and lays out the ghastly accoutrements of the delivery trade on a clean nappy : forceps, cord clamps, a stethoscope; sharp scissors lain on a steel kidney bowl.

She wets two fingers with spittle. Gasp! ‘The old tar’s halfway out the porthole,’ she says to no one in particular, chuckling. Wax-paper is slid between buttocks and soiled bedding, a few bloody snips, two hours’ yelling, some desperate panting

and a new hand for Murray’s Mill is born. ‘Best name him after his dad,’ is said; in case his dad nair comes home is not. Annie says to bathe the mother, the bairn, the bedding in that strict order. But not till she’s washed her own hands and gone.

Mrs Coates at War

(December, 1940)

In drizzly darkness she meets the warden, coal-lit at his brazier. “All well, Mr Wareing?” “Aye, but that were a close one—” and on cue, a siren wails in the distance. The sky above Baxindale’s convulses red as the rock-roof of Satan’s cavern; false dawns of Liverpool, Trafford, Salford; across the firmament bright halos chase after droning devil-silhouettes. “Turning tail, them ones. Done their worst.”

Further along the towpath, ‘Dad’ Bailey, lock-keeper and builder of air-raid shelters : “Mr Bailey.” A short puff, and “Matron.” Better a quiet smoke by the canal than strung last moments in an empty bed or night billeted under Union Street bridge with the missus, the sandbags and the kids. “Hold up, I’ll fetch a little summat—” he comes back out with an orange “—our Nancy queued a whole hour at Hollins but won’t mind it’s you having it.”

They’re nose-to-tail along Old Mill Street already rushing the wounded inside, so Annie quickens her stride. An ARP warden pulls the blackout curtain to one side to let her and the stretcher bearers pass. In A&E everyone except the dying— and Annie—is wearing their gas-mask. She dumps her wet coat in the cloakroom. “They’ve hit Piccadilly.” “Assizes is burning.” Annie says nothing, grabs what she needs, gives a small boy who’s crying the orange.

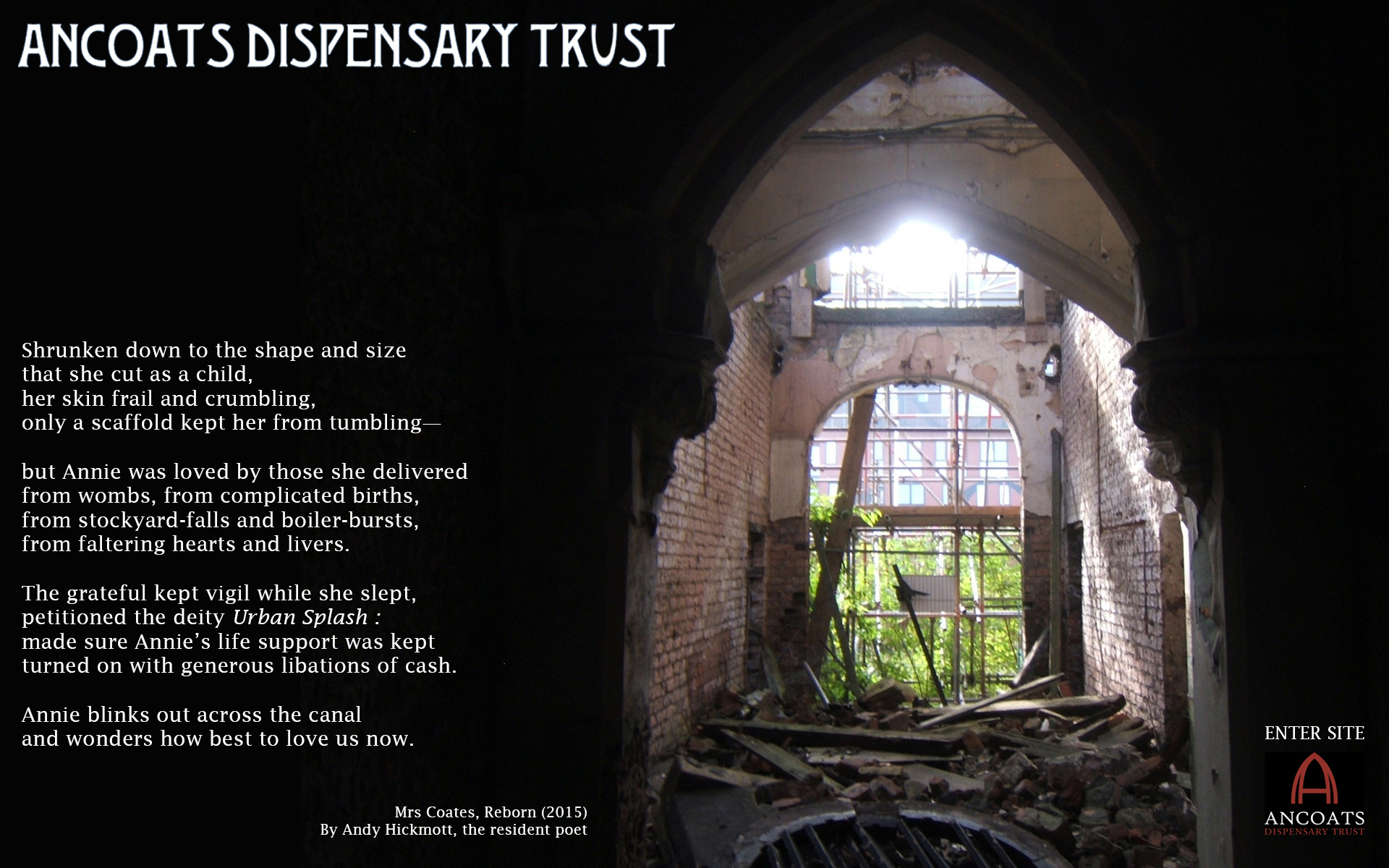

Mrs Coates, Reborn

(2015)

Shrunken down to the shape and size that she cut as a child, her skin frail and crumbling, only a scaffold kept her from tumbling—

but Annie was loved by those she delivered from wombs, from complicated births, from stockyard-falls and boiler-bursts, from faltering hearts and livers.

The grateful kept vigil while she slept, petitioned the deity Urban Splash : made sure Annie’s life support was kept turned on with generous libations of cash.

Annie blinks out across the canal and wonders how best to love us now.